Solidarity Not Charity! DSA Santa Cruz’s Mutual Aid Working Group (a.k.a Love Boat)

The Mutual Aid Working Group—a.k.a. the Love Boat—meets every Sunday morning to distribute food, hygiene, and first aid supplies to the unhoused community in Santa Cruz. Working from an anarcho-socialist theory of mutual aid, the group aims to build networks of social solidarity between the housed and the unhoused to effectively combat anti-homeless politics, meet the essential needs of some of the most disenfranchised folks living in our community, and build networks of support and collective care. In the spirit of mutual aid, operating according to the principle of “solidarity, not charity,” our group seeks not only to address the symptoms of homelessness (hunger, exposure, state-imposed criminality) but to confront its systemic causes (economic precarity, structural racism, neoliberal individualism). We organize campaigns around conflict flashpoints, city policy, and police actions that negatively affect the homeless community, and consider effective socialist responses to structural crises that impact Santa Cruz directly but extend far beyond our city.

The Love Boat emerged at the time of the 2018 Ross Camp’s informal houseless settlement, established in an area at the corner of Highway 1 and River Street between November 2018 and May 2019, when early members began providing supplies to unhoused folks in need. Following the camp’s eviction, people moved to spaces around Highway 1. Soon, the working group had gained its popular moniker: “One day when we were giving out supplies on Coral Street, a man gleefully called out as we approached, ‘Here comes the love boat!’ It was so much better than any stodgy name we could think of!”

In the winter of 2018-19, DSA’s Housing Working Group was developing strategies of tenant organizing in Santa Cruz. They were considering how DSA should embrace all who don’t control their own housing conditions, including renters subjected to outlandish prices in Santa Cruz’s speculative rental market, as well as the unhoused who could never come close to affording local rents. A first step was to meet with residents who were organizing themselves and establishing community guidelines in the Ross Camp, which the city tolerated for several months before evicting folks and fencing the area. “Evict and fence” exemplifies the city’s well-established (non)strategy of continually shifting encampments so as to prevent any permanent settlement in any single area (despite the fact that during the operation of Ross Camp, police citations of homeless folks fell drastically, according to statistics provided by the Santa Cruz Chapter of Science for the People.

That unproductive and harmful policy—directed by the city’s unelected manager Martín Bernal and his staff—was standard in the pre-COVID 19 era. But today, the city’s police-enforced displacement efforts are even more egregious, as they clearly violate CDC public health guidelines, intensify precarity and desperation, and endanger us all by continually evicting populations of people without providing adequate low-income housing, emergency shelter and adequate support services for the area’s houseless population (including those newly joining the ranks of the unhoused after their homes burned down in the recent wildfires). While so far there have been no Covid’s outbreaks in houseless encampments in Santa Cruz, it is without thanks to the city’s callous approach, backed up by xenophobia and classist nimbyism and private property interests.

Unlike several progressive cities, such as Reno, Oakland, and Chico, which have instructed police to discontinue sweeps and clearing of encampments—which run counter to public health best practices in the era of Coronavirus, according to the National Homeless Law Center—Santa Cruz persists in camp evictions, including the recent expulsion of Food Not Bombs from their downtown location, seen by the city as a “public health nuisance.” In justifying these evictions, the city often refrains from collecting trash, failing to aid residents’ efforts to keep their spaces clean, in what appears to be a cynical attempt to link houseless folks to out-of-control waste buildup, which in turn legitimates police actions in the name of hygiene as seemingly the only solution. In response, the Love Boat has organized their own clean-ups in the vacuum of the city’s cruel withdrawal of services.

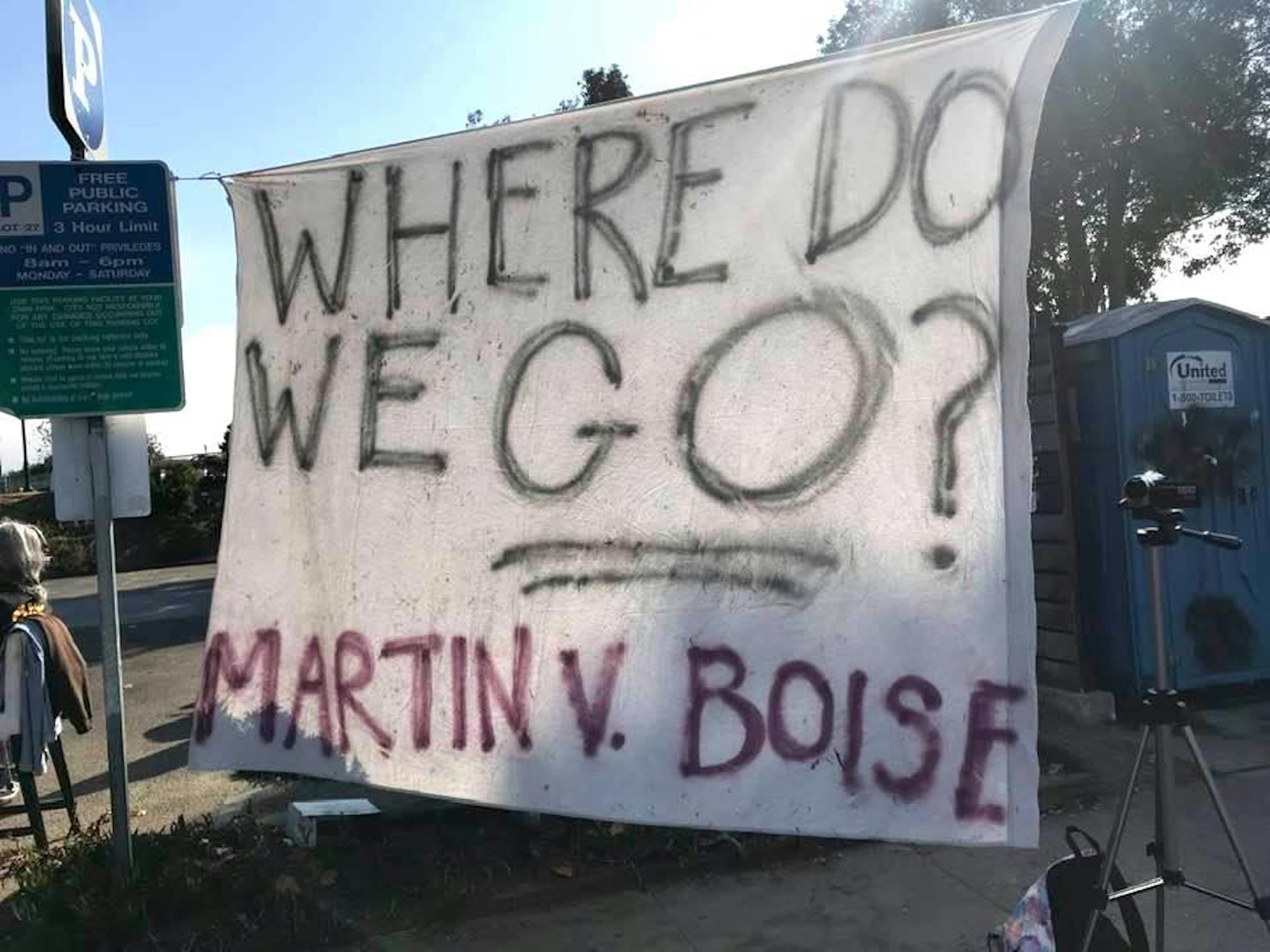

Santa Cruz’s approach contradicts Martin v. Boise (2018), a landmark supreme court decision that deemed unconstitutional the punishment of houseless people for sleeping in public space in the absence of viable alternatives. While the city has gone to lengths to avoid contradicting the ruling technically by not making it illegal to sleep here or there, they have violated the law in spirit by enforcing trespassing restrictions and ticketing folks in public space, in the hopes of disappearing the homeless population (following a strategy notably used in Eureka where Police Chief Andy Mills was formerly employed, as we have learned from Eureka’s activists). This practice has also been complimented by the city’s fencing off any and all available public space, including Louden Nelson Center and Grant Park, the Post Office, and the Town Clock, and posting warning signs in places like the Public Library and the Civic Auditorium that essentially make it a citable offence to sleep on those grounds after 6pm or on the weekends (in addition, our City Hall has been re-landscaped to dissuade sleepers, according to a practice common in larger cities of creating “defensible” public space).

The city’s effective criminalizing of the shelterless actually constitutes a large percentage of city policing—approximately 60% of all police calls respond to situations involving unhoused folks, where armed police are unnecessary and may potentially lead to violence. Data acquired through the California Public Records Act show that between January 2018 and June 2019 there were over 11,000 citations for minor incidents like remaining on bus property after requested to leave; limiting access and use of public property; failing to vacate park property; possessing an open container of alcohol in public; and obstruction of movement in public ways. Deploying the police to enforce a hostile environment, Santa Cruz city’s actions, moreover, directly conflict with justice-based and compassionate approaches to houselessness, such as Philadelphia’s, where fifty unhoused families recently won a six-month landmark campaign in forcing the city to deed vacant houses to a community land trust so that they can find places to live. Indeed, another world is possible!

Countering the city’s arbitrary, violent, and punitive measures—which are often accompanied by needless ticketing and court summonses that punish the precarious and their allies with fees and fines—the Love Boat collaborates with the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz, focusing on building autonomy, acceptance and unconditional support of others, saving lives, and cultivating positive change. Love Boat also works with Food Not Bombs, the SubRosa collective and the Hub for Sustainable Living, YARR (Your Allied Rapid Response), Santa Cruz County Mutual Aid, Santa Cruz Tenant Power, Grey Bears, and Santa Cruz Cop Watch. It collaborates regionally with Watsonville’s desolasol colectiva and DSA chapters in San Jose, East Bay, Central Coast, and San Francisco.

During its weekly distributions, the Love Boat offers homeless/houseless folks vital supplies, including individually prepared lunch bags, bottled water, personal hygiene and medical supplies, tents, sleeping bags, and information regarding rights and local institutional resources. Narcan (Naloxone) is distributed, used in treating narcotic overdose in emergency situations, and has already saved lives in Santa Cruz. The group has also raised bail funds and organized jail and court support when necessary. Members have participated in advocacy, pressuring the city to adopt fairer policies toward unhoused people and to provide better services and emergency accommodations.

During the pandemic, it has raised funds to buy thousands of N95 masks to protect against the virus as well as toxic air from the recent regional wildfires. Hundreds of masks were also donated recently to Watsonville comrades in desolasol colectiva, who distributed them to farm workers facing little choice but to work outdoors during periods of dangerous air quality owing to economic necessity (this action was coordinated with a recent central coast mutual aid event for San Benito Santa Clara farmworkers at the Ochoa labor camp in Gilroy). These vital donations come from member gifts, anonymous contributions, and collection jars at coffee shops, including our local member-owned Tabby Cat.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing the Love Boat is providing assistance when Santa Cruz city and its police are intent on maintaining a hostile environment to deter houseless folks. During their repeated sweeps accompanied by threats of legal and economic punishment and needless arrests—according to a one-size fits all use of policing and incarceration—property is frequently confiscated and destroyed. At times this includes sending sleeping gear and tents, newly donated by the Love Boat, directly to the land fill. Instead of working with community organizations building resources of people power in providing vital supplies to the city’s most needy community members, the city prefers to wage a battle against all such efforts, appropriating community funding for policing that could otherwise be funneled to support more community-based approaches to the city’s homeless services including mental health, addiction recovery, education, and affordable housing.

An additional challenge is that harsher federal immigration policies have complicated aid distribution through official channels. With stricter rules, many feel apprehensive about seeking assistance owing to fears it could jeopardize their own or a family member’s immigration status. That makes informal distribution networks ever more significant. Without getting bogged down in unnecessary paperwork, groups like Campesinx Womb Care Project (@campesinxwombcare) are able to hand out supplies to farmworker women at locations that are publicized through trusted community networks rather than through official channels. In Santa Cruz, a similar informal supply chain has delivered food donations to the Beach Flats Community Garden, with Love Boat members stepping in to help ensure that the weekly food deliveries continued during COVID.

Directed by its unelected city manager, backed by a majority of city council members, supported by the conservative Downtown Business Association and local reactionary groups spewing xenophobic and anti-homeless bile on sites like Nextdoor.com, the city prefers to invest in policies supportive of real estate speculation, gentrification, policing, and private property economic interests, above peoples’ lives, public health, and grassroots community participation in democratic governance.

Yet DSA is fighting back! Drawing on well-established principles of collective care, the Love Boat’s commitment to “solidarity, not charity” entails a mode of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government, but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable. The unhoused can be political agents and allies in struggle against the brutality of capitalism, rather than depoliticized victims in need of charity. As such, mutual aid defines a form of prefigurative politics, where we realize a future now in the very place we are living, working, and caring for each other, rather than for capital. As Dean Spade and Ciro Carrillo explain:

“Charity is when rich people and institutions give tiny crumbs to poor people to make themselves look better. Usually there are a lot of strings attached to what they give. Like giving only to mothers or only to children, only to sober people, or only to people of faith. Charity rides on the idea that rich people or social workers should decide who is a deserving poor and who is the undeserving poor. And that rich people can put conditions on the housing or food or cash they give poor people. Charity blames poor people for poverty. Mutual aid blames the system for making people poor and says everyone deserves everything they need. Charity affirms the existing distribution of wealth and life chances; mutual aid challenges it. Charity is top-down, mutual aid is horizontal. Charity is about control, hierarchy, and isolation. Mutual aid is about solidarity, liberation, and participation. Solidarity not charity!”

Mutual aid defines a form of “everyday communism,” according to the late great David Graeber, one that occurs in the small gestures enacted daily among friends, family and community, including actions of common caretaking without expectation of return. In this version, communism isn’t abstract or a distant ideal, still less top-down tyranny, but a lived practical reality that already occurs in a million acts of kindness and love performed by comrades at work, in families, and in community and informal spaces—including in houseless encampments—in the name of mutual survival and creative cooperation. As Graeber once said, “To create a new world, we can only start by rediscovering what is and has always been right before our eyes.” The Love Boat is committed to cultivating that new world—a world that values the lives of the many over the profits of the few. We are always looking for more folks to join us. If you’re wanting to help out and join in building that world, please get involved!

Mutual Aid Working Group (a.k.a Love Boat).