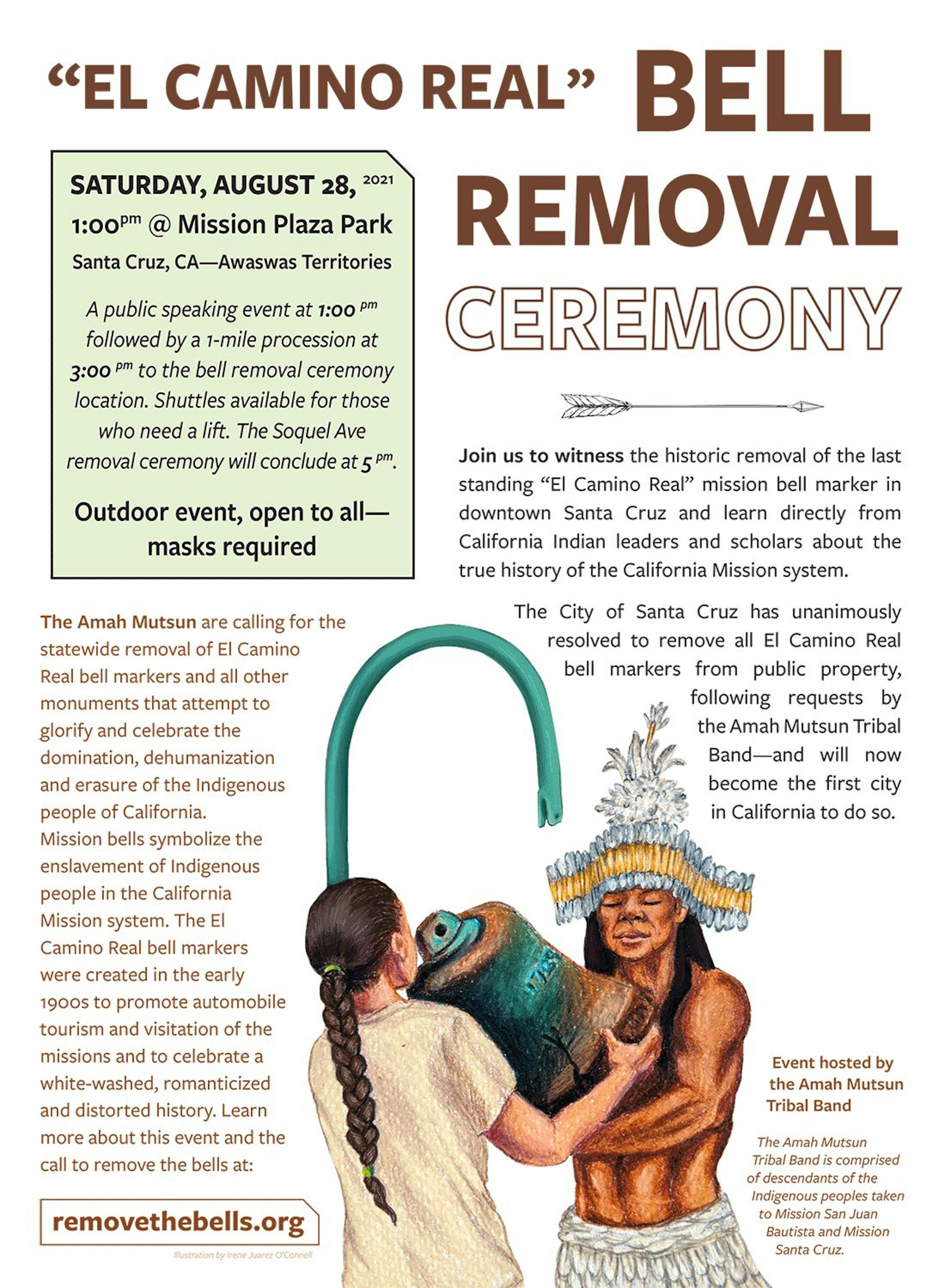

In June of 2019, administrators at UC Santa Cruz acquiesced to the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and their request to remove an “El Camino Real Bell” commemorating Spanish colonial history in California, which sat in a forested area in the middle of campus. A year later, during a Santa Cruz protest march inspired by #BlackLivesMatter, Indigenous calls for decolonization, and the growing movement to remove white supremacist and colonial monuments across the nation and internationally, activists tore down another El Camino Real bell located at the Mission Santa Cruz Plaza park.

Chairman Valentin Lopez of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band speaks in front of an El Camino Real bell before its ceremonial removal from the campus of UC Santa Cruz on June 21, 2019. The cast-iron bell marker is one of hundreds in the state which commemorates the California Missions. The Amah Mutsun and other California Indigenous people view the bells as racist symbols that glorify the violent colonization of their ancestors. (Photo: Cody Glenn)

Some are describing these removals of public monuments and statues as acts of historical erasure or as manifestations of so-called ‘cancel culture.’ But are they? As an historian, I sympathize with these concerns regarding ‘historical erasure.’ However, the concept of erasure needs to be unpacked and understood in proper context, historically and politically. We need to be asking – what exactly has been erased? In the above cases, it is actually the Indigenous history of these lands that has been continually erased, including by these very historical monuments.

The climate around these protests has inspired local initiatives to reconsider historical monuments, including an ultimately successful effort to remove a portrait bust of George Washington from downtown Watsonville. Cabrillo College is considering changing its name from its current colonial reference. And last November, the Santa Cruz City Council voted in favor of removing the last remaining El Camino Real bell from downtown (located at Soquel and Dakota streets).

In fact, the mountains, rivers, and valleys all had names known to the Native peoples who lived here for thousands of years prior to European arrival. But when the Spanish came to these beautiful lands, rather than listening and learning from the people who had long called this place home, they imposed their values and culture upon everyone and everything. Spanish colonialism, like all colonial projects, involved a violent process of destroying, dominating, renaming and subjugating Indigenous peoples and lands. So began the erasure of local Indigenous names and histories. The village in modern downtown Santa Cruz was known as Aulintak (“Place of the Red Abalone”), Watsonville was home to the village of Tiuvta (“Place of the Elk”), Hollister was the village Kotretak (“Place of the Gopher Snake”), and so on. But today, only the Spanish names are recognized by most local residents.¹

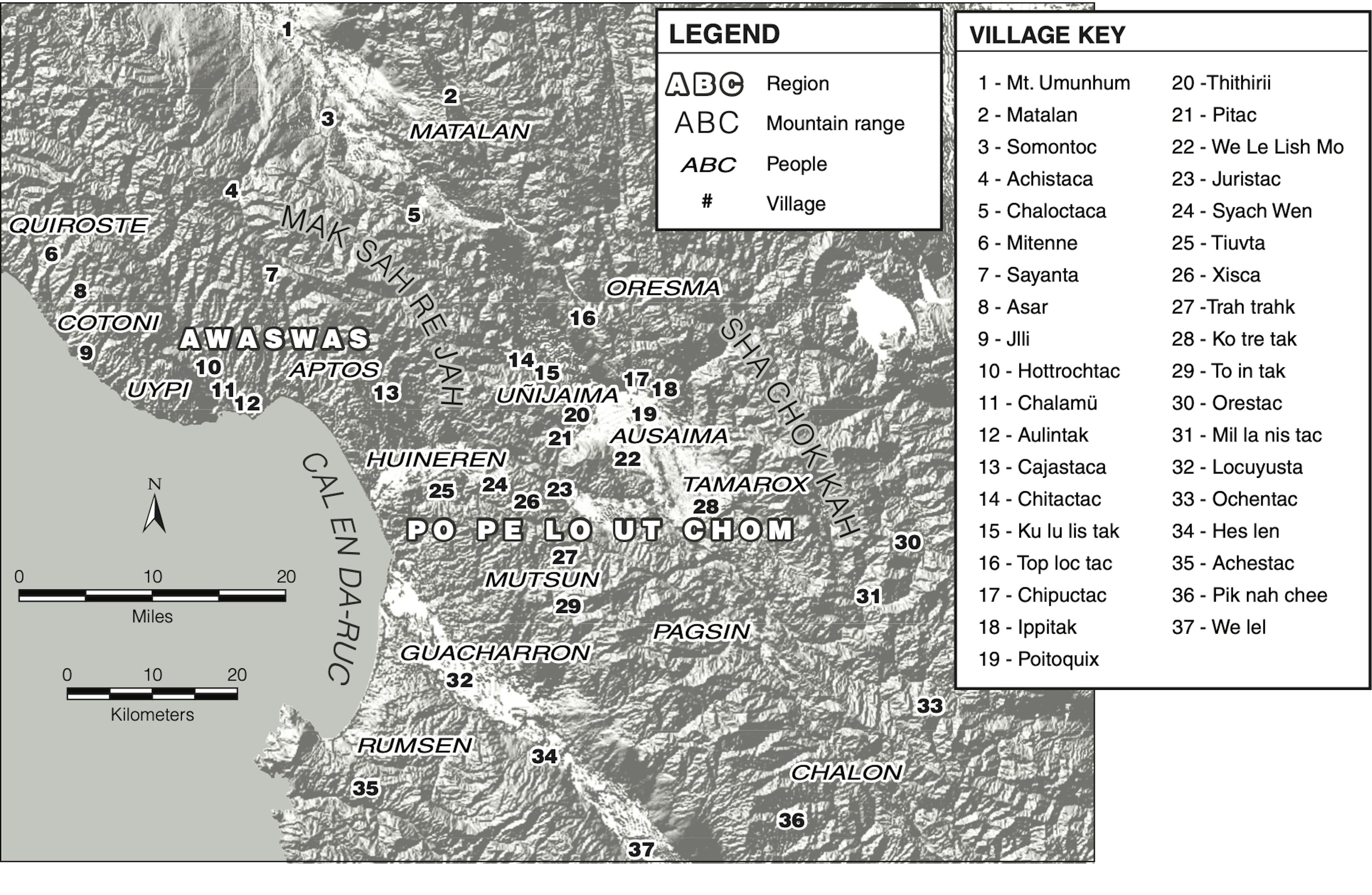

Popeloutchom (Monterey Bay Area) Indigenous landscape with original names and village approximations. (Originally designed by Ed Ketchum, Amah Mutsun Tribal Historian, adjusted by Martin Rizzo-Martinez, digitized by Stella D’Oro)

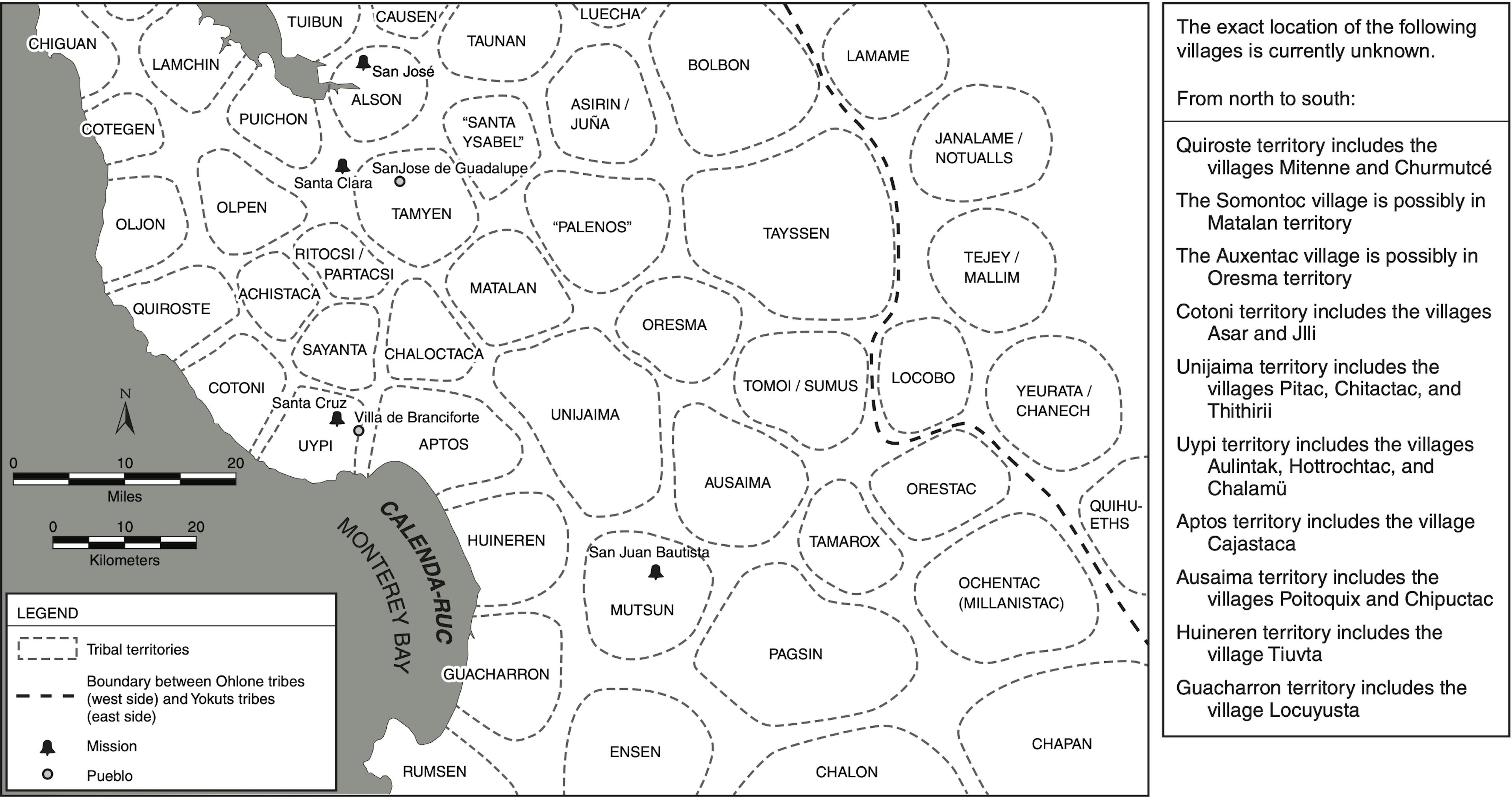

Popeloutchom (Monterey Bay Area) Indigenous landscape showing approximate tribal territories prior to Spanish colonization. (Original version by Randall Milliken, adjusted and reshaped by Martin Rizzo-Martinez in consultation with Ed Ketchum, Amah Mutsun Tribal Historian, and digitized by Stella D’Oro)

Missionaries similarly imposed Spanish names on the tribes themselves, re-naming them using the names of Catholic saints. At Mission Santa Cruz, the missionaries referred to the Uypi tribe of Santa Cruz as San Daniel. The Aptos people south of the Uypi, they called the San Lucas people. The Cotoni to the north of the Uypi were called the Santiago people. Similarly, the process of baptism involved assigning Spanish names to people on top of their Indigenous ones. The process of re-naming and the imposition of Spanish Franciscan names and values upon Indigenous peoples was an essential part of the colonial process.

Mission Santa Cruz was founded in 1791 and was eventually closed down in the 1830s. In that period, over 2,289 Native people received baptism at the mission. By the time the mission officially closed, 2,078 had been buried. Even taking into account the many who would have died of natural causes, over 90% of those baptized at the mission—many as children—died by the time the mission closed after its forty-year existence. A smallpox epidemic swept through California in the late 1830s, taking out many of the elder surviving generation and leaving just over 100 Mission Santa Cruz survivors by 1840.

For Indigenous survivors of the missions, things worsened further in California of the nineteenth century. The era of U.S. occupation that began in 1848 resulted in policies of outright genocide. This came through a combination of laws and policies supporting the killing of Indians by vigilantes and soldiers, the capture and enslavement of Indigenous children, the exclusion of legal and political rights and avenues for redress, and more. For many surviving families, their children frequently attended special boarding schools, introducing new traumas through programs focused on “killing the Indian to save the man.” And yet many persevered despite these genocidal and assimilationist policies, due to their strength and ingenuity, in spite of the terrible circumstances they faced.

The politics of history: Graffiti by activists contesting the false commemoration of the Santa Cruz Mission on a monument from 1982 created by California’s State Department of Parks and Recreation and the Santa Cruz Historical Society, June 11, 2020 (Photo: Alex Darocy)

By the early 1900s, the erasure of this history was made official when a consortium of Californian tourism boosters, women’s club members, and automobile club sponsors formulated a plan to sell tourists on California by drawing attention to the missions, which at the time were crumbling in disrepair. They promoted and romanticized the story offered by Franciscan scholars, one that quicky became the dominant—but false—narrative of Californian history. Their version was a sanitized and carefully manicured version of Californian history that centered on an excessively romanticized version of the Spanish Mission era.

This romanticized narrative manifested itself in geographical symbols to help promote tourism in California, which included the El Camino bell markers. Beginning in 1906, the California Bell Co. began to place these bells along what would become Highway 101 to promote a newly developing automobile centered tourism. Like so many other California highways, this route was paved on top of former Indigenous trade routes, further erasing this history. The invented idea of the El Camino Real was itself as fictional as the mythical mission narratives. The harsh realities of Spanish colonialism were glossed over with more palatable, fictitious, stories celebrating the presence of beneficent padres bringing civilization to Native people. The saccharine depictions of benevolent missionaries saving the souls of “savage Indians” is epitomized by the "sugar-cube missions”—the models of mission architecture children are commonly asked to build in the in 4th grade classrooms of California public schools—where education indoctrinates settler colonial culture still to this day.

And yet, at the same time that the public embraced these fantastical versions of history, the descendants of mission-surviving families were not consulted, and their perspectives were completely left out of the accepted narratives. These families struggled to find ways to survive in a society that had openly called for the elimination of Native people. Many taught their children to hide their Indigenous heritage from others, and some would take refuge in their Spanish names, the Spanish language, and their facility with Mexican culture, which were legacies from the mission era that they utilized in order to survive in worsening circumstances of anti-Indigenous racism.

By the early 1900s, the population of Native Californians reached its nadir, with fewer than 16,000 individuals recorded, a tiny percentage of the 300,000 plus estimated prior to Spanish arrival.² Around the time, when the Franciscan version of a pastoral Californian history beginning with the arrival of exalted missionaries was becoming the accepted narrative, ethnographers and scholars like C. Hart Merriam and John P. Harrington (among others), interviewed and recorded the stories of the mission survivors. The stories they told stood in stark contrast with the romanticized mission myths.

Mission Santa Cruz survivor Lorenzo Asisara told an interviewer in 1886 about his Cotoni (a tribe on the northern Santa Cruz coast) father’s participation in the assassination of Padre Andres Quintana, after the padre had beaten two young men nearly to death. Quintana had a specially made whip fitted with wire on the ends so that he could inflict deeper wounds upon his victims. Asisara recalled Padre Luis Gil y Taboada, and how the latter passed syphilis to the Yokuts women at the mission in acts of sexual violence. He spoke of how Padre Olbés forced an infertile Yokuts couple to copulate in his presence, inspected their naked bodies against their will. To punish the woman for her apparent infertility, he forced her to carry a wooden doll, a practice reported at other missions as well.³

Ascención Solórsano, an honored ancestor of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band who survived Mission San Juan Bautista, shared graphic stories of the violent capture of Yokuts families and of abuses that took place within the mission. In one story, Solórsano related that she had heard “that they used to wall people up, they made a hole in the adobe wall only big enough to accommodate the body of the person and they put the person in there and left him there to die and dry up… especially to women. The priests always picked out a pretty girl, and if she did not let herself be used by the priests, they would wall her up, or else they would do away with her in some other way.”⁴

Some historians and skeptics might doubt and cast aspersions on Solórsano’s story, pointing to the lack of substantiating evidence (despite the fact that nobody has ever analyzed the adobe for bone remnants). Indeed, many tend to dismiss oral histories. Yet horrific stories such as these were shared by mission survivors. They speak to the immensity of the trauma, the pain and terror inflicted at the missions, and the frequency of sexual abuse. It is important to consider what we know today about the difficulties that victims of traumatic sexual assault have in sharing their stories. How difficult must it have been for Solórsano, Asisara, and others to relate these stories to white ethnographers, and how important must it have been for them to insist on recording their testimonies? How many similar stories have been passed down through Indigenous families who survived the missions?

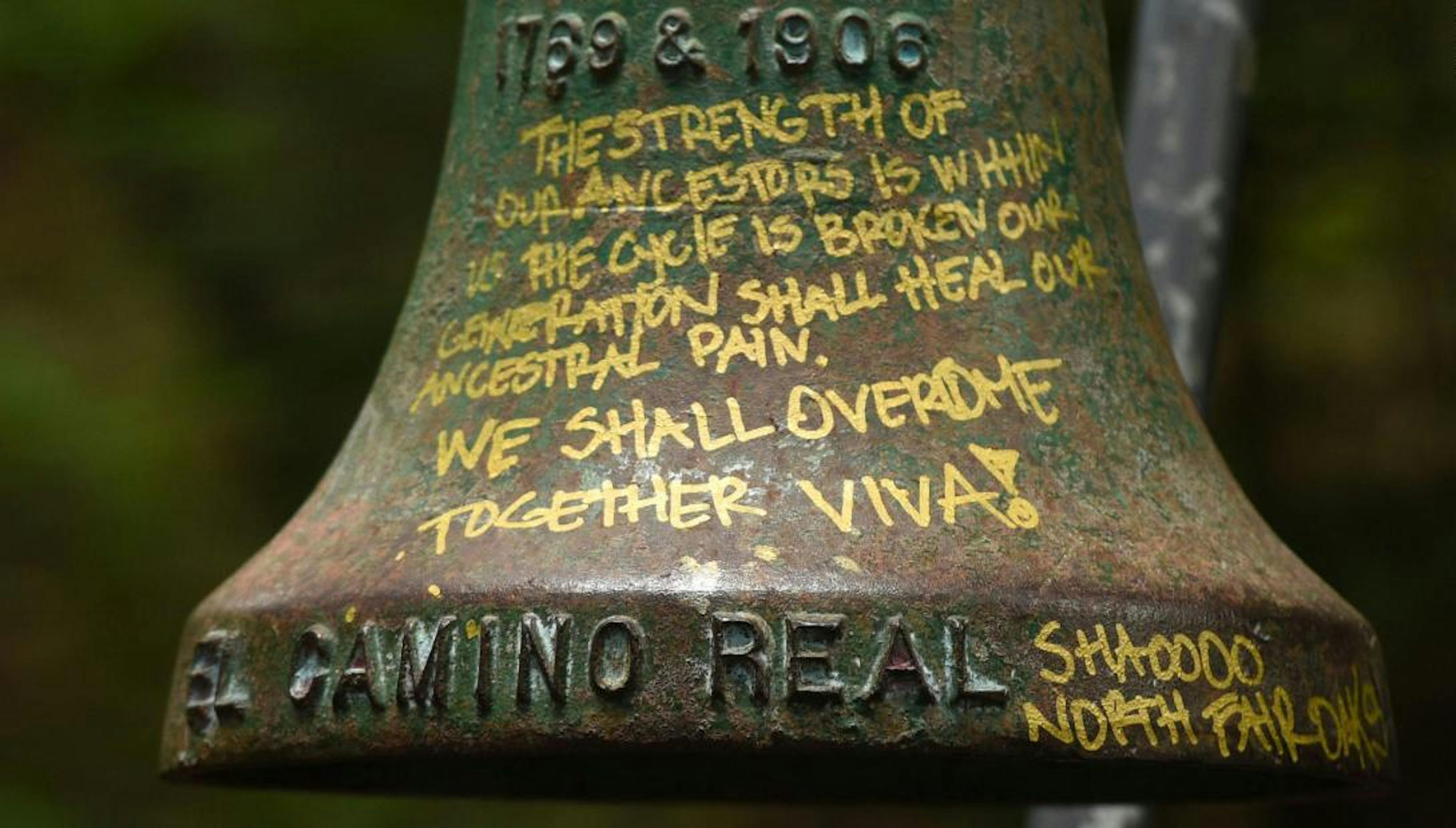

Graffiti on the UC Santa Cruz mission bell, shown just before its removal on June 21, 2019, in Santa Cruz, Calif. (Photo: Cody Glenn)

Today, some people are still reluctant to review and correct the feel-good, fictitious mission narrative. California’s education system has long focused on teaching mythical mission history to 4th graders. While California is beginning the process of including Native Californian histories in the curriculum, many well-meaning educators and parents are reluctant to see changes to educational curriculum, often insisting that we cannot subject children to these kinds of terrible stories. But what about young Native children who have to repeatedly hear and experience the impacts of the false narratives and lies of settler colonialism? Others argue that this is a society-wide pattern of “ritual avoidance” and that these hard histories can and must be taught. If these truths are too difficult for fourth graders, why do we have to teach the history of the missions to children this young? Why not teach the true story of missions when students are old enough to grapple with these disturbing truths? Because otherwise, by continuing to teach lies and whitewash history, we are participating in the perpetuation of untruths that allow colonial violence to go unaddressed and instead to be celebrated.

As for dealing with statues and symbols like these bells, it is true that changing the names of things, taking down traumatic markers, and removing statues commemorating perpetrators of trauma and genocide does not actually change the past. But while we cannot go back and change these traumatic events, we are still living today with the legacies of colonialism and genocide. And while many Californians have the luxury to embrace the romanticized fantasies that the bells offer, for many Native mission surviving people, they represent a visceral trauma, as these markers serve as reminders of their ancestors’ subjugation. Recent studies have shown how traumas are passed down through generations, meaning that if we want to find peace today we must reckon with our past. It is up to us to decide how we choose to deal with its telling – whether to ignore and justify violence or to face the hard truths and work toward a better world.

How can we—as a society, as a country, as a state, as people—come to terms with this history of colonialism, brutality, and genocide? How can we honor this history and work to make amends, rather than perpetuating injustices and erasures? The answers aren’t easy, but I do know that we must begin by listening to the people who have endured this violent traumatic history, thanks to the strength, resiliency, and ingenuity of their ancestors. If they demand the removal of these symbols, these emblems of colonial violence, then we who oppose that violence must join them in their struggle, working in solidarity with Indigenous decolonial aims. Removing the El Camino Real bells is a first step towards acknowledging the true history.

¹ The name Aulintak comes from two sources. The first mention appears in an 1890 interview with Mission Santa Cruz–born Lorenzo Asisara conducted by E. L. Williams, in E. S. Harrison, History of Santa Cruz County (University of California Libraries, 1892), 45–48. Asisara mentions “Aulinta” as the name for Santa Cruz given by the Uypi. “Aulintac, the rancheria proper to the Mission” is recorded by ethnographer Alexander S. Taylor in his article on the Awaswas Ohlone language. See Alexander Smith Taylor and Ray Iddings, The Indianology of California (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015), 6. Taylor credits this name (along with others) to a currently missing letter from Friar Ramon Olbes to Governor Sola, dated November 1819, “in reply to a circular from him, as to the native names, etc., of the Indians of Santa Cruz, and their rancherias.” It is also repeated as “Aulin-tak” by Alfred L. Kroeber, presumably taken from the Taylor records, in A. L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (Dover, 2012), 465. The translations for the names Tiuvta and Kotretak come from correspondence with Ed Ketchum, Amah Mutsun Tribal Historian, email to author, September 11, 2019.

² These numbers are reported by the State of California’s Native American Heritage Commission: http://nahc.ca.gov/resources/california-indian-history/

³ The transcriptions of these interviews with Lorenzo Asisara are found under Jose Maria Amador, “Memorias sobre la historia de California,” Bancroft Library, BANC MSS C-D 28, 58–77. These can be accessed online: https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/hb500007d5/?brand=oac4. The use of wooden dolls to psychologically punish women was also reported at Mission San Gabriel by Antonia Castañeda, “Engendering the History of Alta California, 1769–1848: Gender, Sexuality, and the Family,” California History 76, no. 2–3 (1997), 234.

⁴ The J.P. Harrington interviews with Ascención Solórsano are in the John Peabody Harrington Papers: Costanoan, in the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian Institute. These can be accessed online here. The cited story is found in Reel 59, image 874 of 1141.

Martin Rizzo-Martinez is a historian who has taught classes at UC Santa Cruz, Cabrillo College, and to inmates at Salinas Valley State Prison. He works closely with the Amah Mutsun and other local tribal partners. Before returning to Santa Cruz, he was a UC Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellow. He has published several articles on local Native American history, and his book manuscript, We are not Animals: Indigenous Politics of Survival, Rebellion and Reconstitution in 19th Century California (including a foreword by Amah Mutsun Tribal Chair Valentin Lopez) will be in print later this year. (The two maps appearing in this essay were created for Rizzo-Martinez's forthcoming book).