Ex Machina Redux: Refusing the Space Billionaire Technological Sublime

A few weeks ago I opened The Guardian to find that the voice of my middle-aged generation, Douglas Coupland, author of the book that gave Generation X its name, had posted an article “In Defence of Elon Musk.” That anointed spokesperson for a generation known for its caustic irony, unironically endorsed the “Silicon Valley Übermensch” as “the smartest man in any room anywhere.” He then went on to assert that such sins as the abuse of one’s employees, stinginess, and lack of political vision are dwindled by the great man’s luminous contributions to technological progress.

Elon Musk, founder, CEO and Chief Engineer of SpaceX

This travesty of an op-ed made me think back to a profound moment of my Generation X youth. In my 7th grade English class, we were all compelled to watch a live broadcast of the space shuttle Challenger’s take off, which unexpectedly included its disastrous explosion in the troposphere moments later. Soon after, the punk singer Jello Biafra interrupted the shibboleths of national mourning by putting out a spoken word record with a piece called “Why I’m Glad the Space Shuttle Blew Up.” The Challenger’s success, Biafra claimed, would have been a gateway to the pursuit of environmentally devastating and perhaps genocidal ventures in space. He did not glory in the death of Christa McAuliffe and the rest of the crew, but neither did he want to mourn a mission that, given its patriotic and geostrategic functions, could lead to an increasingly ambitious space program, eventually risking the lives of millions by carrying nuclear weapons-grade plutonium capable of mass destruction on future operations. This was no time for thoughts and prayers, Biafra implied, but for staunch refusal to be enthralled and controlled by the militarization of space and its technological sublime.

Biafra’s words were a blasphemous example of the utopian side of Generation X’s much maligned cynicism. We were not just sullen brats, though we were sometimes that. Our negativity could be a sign of righteous anger worn to bitterness. Hope had eroded into snark in the face of a ghastly Reaganite horizon that fused Pollyannish “optimism” with death-driven technological developments and social policies.

Cosmonauts Elon Musk and fellow rats appear in Soviet style-propaganda

Now we are told by our fearless leader Coupland, that it is time to grow up and get with the program. Billionaire space wizards like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson represent the most forward-thinking, ambitious, entrepreneurial forces of our society. They are looking to the future, while we all tread water or admit defeat. Our paltry demands for housing, food, medical care, a clean environment, and free time to create and flourish, pale against the monumental visions of our space overlords.

That is, forget the costs and look at the vision. There will be long, thick phallic rockets, 400 feet high, that will “ferry 100 colonists at a time to Mars over a period of decades.” Once we’ve arrived at Mars, we will begin by living in glass domes, but eventually the planet will be blasted with nuclear weapons, accelerating the process of terraforming. Or maybe instead we will surround Mars with giant mirrors that will intensify the sunlight reflecting on the surface. (How this will be done by an organization that couldn’t fix their space toilet is yet to be seen). No matter, earth, as Bezos proclaims, will become a pristine national park and tourist center, as we move the world’s entire population out to space colonies in orbit. These will be long cylindrical tubes floating between Earth and the moon, which will somehow be rigged out to be like “Maui on its best day, all year long…” And if the colonization of earth and space are not enough to blast us out of meatspace, we can follow Zuckerberg into the metaverse, “a reality so virtual that Facebook hasn’t yet destroyed it.”

Musk blasts off, cowboy style, with his Space X rocket, evoking Slim Pickens riding his nuke to orgiastic destruction in Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Meanwhile, the space billionaires continue to ruin the planet. They destroy our environment by leaving huge carbon footprints, collaborating with oil and gas companies (including by developing AI and algorithms to make extraction more efficient), enacting coups wherever they want, and pretending to be the emblems of environmental stability while undermining real solutions. They ruin the lives of workers by denying them unionization, threatening their lives with unsafe working conditions, and terrorizing whistleblowers. They hoard money that could be used otherwise to solve social problems. They advance privatization while draining the public coffers. They deepen the insidious hold of our military industrial complex, ICE, police, and surveillance technology. They intensify housing crises and homelessness. And they pollute our intelligence with anti-social, feudalistic, libertarian, eugenicist views.

Like these would-be gods, Nathan Bateman, the central character in the 2014 sci-fi horror film Ex Machina (written and directed by Alex Garland), has reached the outer-most regions of human accomplishment. In this case, the frontier is human consciousness, but, as with our real-life space billionaires, the spectacle of scientific discovery is a mere cover for anti-social machismo and greed. While the movie is nearly a decade old, its futurism remains ever prescient, given how well it predicts many of the crises of our conflicted present. It is well worth returning to today, in order to reconsider its lessons in light of the present conjuncture of technodystopia, biopolitics, and oppressive billionaire futures.

When watching this beautiful film with its slick design and detailed, futuristic imagery, it is easy to be distracted from Nathan’s power-obsessed madness. Instead, we are diverted with philosophical, ethical, and scientific questions about artificial intelligence. But focusing on these speculations misses the point that Jello Biafra made so rudely. We should not get distracted by the technological issues Ex Machina raises.

At a time when billionaires blast off into space as the world burns, we must look at the film as an exploration of what historian of science Leo Marx called “the technological sublime”—the destructive, entrancing effects of technological progress. Critically reproducing those effects, the film shows how those who suffer under technocratic capitalist rule are gendered, divided, dehumanized, and duped.

In the film, the reclusive tech CEO “invents” a cyborg, Ava, who is not literally human. But within this logic of power and technocracy, we can’t doubt her humanity. She is both an emblem of the hyper-control technological capitalism wields over our lives and the sustained hope for feminized “cyborgs” to develop revolutionary subjectivity and independent agency. In this film, which is staged as a “prison break” by an imperiled robot, the cyborg offers an allegory for any person who is inextricably embedded in modern technology and wants to use that technology towards her own freedom.

In her quest for autonomy, our “machine” is purely human. Meanwhile, our rulers, though flesh and blood, have become “machine.” Like the “soldier males” of previous authoritarian regimes, figures like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, as fictionalized by Nathan Bateman, are rigid and implacable, made more dangerous by their bromantic overtures and veneer of laid back camaraderie. Despite the pretense of loose, casual attitudes, these ciphers represent a desire for pure quantification, and the end game is an abstract utopia, a singularity, where even the pleasures of eating are left behind.

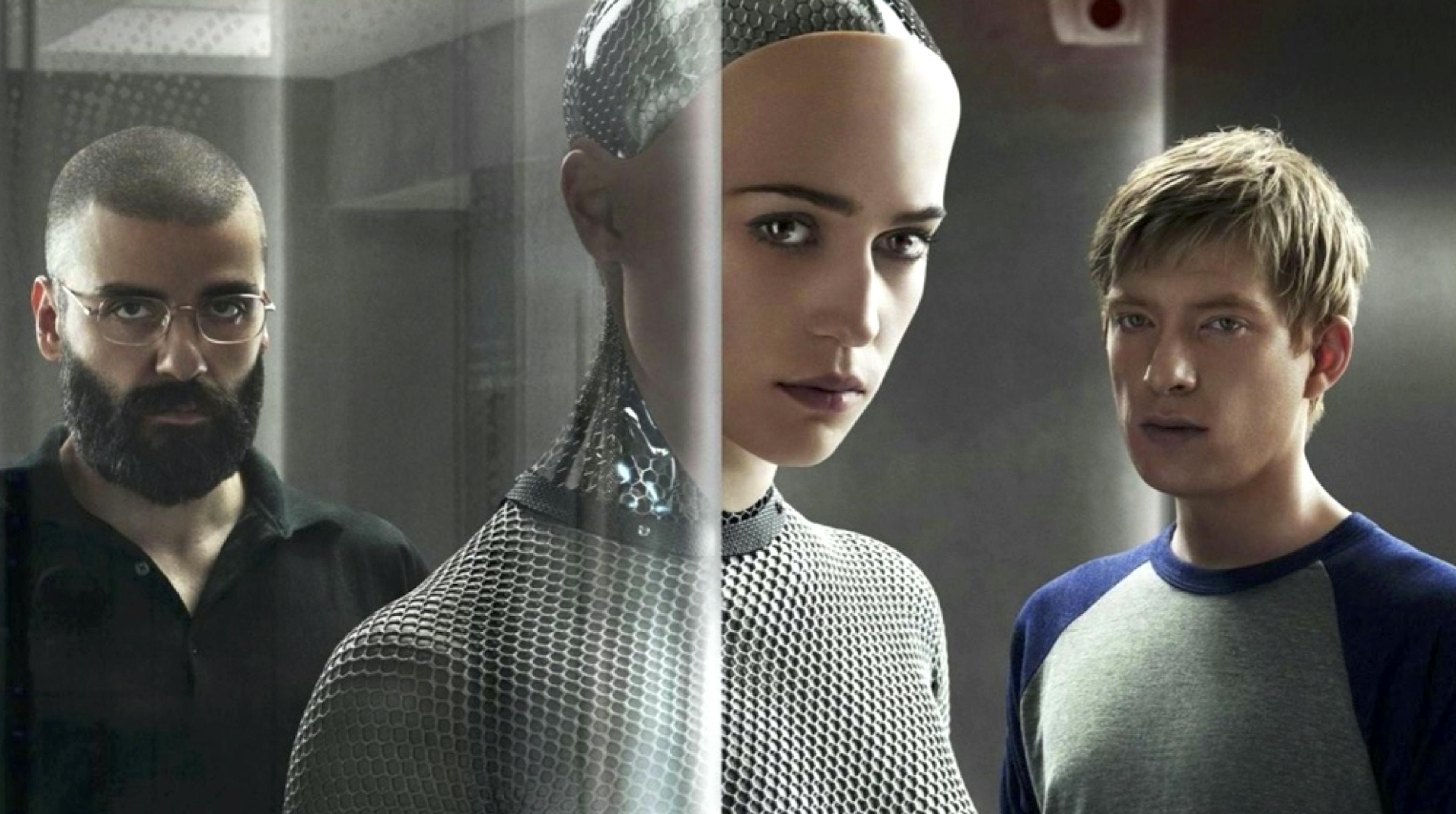

Programmer Caleb Smith (played by Domhnall Gleeson), visits buff CEO Nathan Bateman (played by Oscar Isaac) at the latter’s luxurious, isolated home in Ex Machina.

Ex Machina cuts through the mythological web spun by techno-utopian pirate libertarianism by paring down a story, one that is meant to overwhelm and stun us with its complexity, to a chamber-play involving four characters: Nathan, the billionaire tech wizard overlord, Ava, the feminized affective laborer, Kyoko, the racialized, super-exploited fembot, and Caleb, the white, male, information worker whose interests lie with those who are feminized and exploited, but who is seduced by the fantasy of meritocracy to believe that Nathan’s power will extend into his own orbit.

The film has been compared to Frankenstein, an exploration of the hubris of a man who invents life and becomes a god, but less has been said about its relationship to the suppressed narrative at work in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, a film in which a capitalist kingpin creates a contest, luring children into his fortress with the promise of great riches, but whose actions prove to be sinister and murderous. In this case, the contest is held by Nathan, the founder and CEO of Blue Book, “the world’s most popular internet search engine.” Caleb is the lucky winner who is chosen to spend a week living with Nathan in his remote bunker where he will gain exposure to the great technological achievements under development there.

The remoteness of Nathan’s home/laboratory brings to mind the space stations dreamed up by Musk and Bezos (these recalling space plans of orbital settlements investigated by Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill in the 1970s, plans that gave form to still earlier sci-fi imaginings). These sites of “progress” have nothing to do with humanity and everything to do with a solipsistic frontier colonial mentality. In Nathan’s fortress, isolated from any collective project, madness festers. From the moment he arrives by helicopter, Caleb is deluged by red flags pointing to his host’s sociopathy. His first encounter with Nathan is menacing, as he spots his host working out and flexing his intimidating muscles. After this, Caleb is led to his claustrophobic, windowless room and Nathan lets him know that he is locked out of and locked into select parts of the building. Yet even though Nathan doesn’t bother to disguise the fact that his guest is trapped in isolation with a brutal and unpredictable alcoholic, Caleb ignores the warning signs, instead choosing to believe in Nathan’s slick, friendly veneer. The way Nathan explains Caleb’s key to him says everything about these obfuscatory dynamics:

The first thing I should explain is your pass. It opens some doors and not others. And that just makes everything easy for you, right? …Because you’re, like, in someone’s house and you’re, like, can I do this, can I do that? And this card, it just takes all that worry away. You try a door and it stays shut, it’s not for you. You try another door and it opens, then it’s for you.

Here, Nathan frames Caleb’s lack of choices and limited possibilities as freedom and ease. Like the company he runs, a search engine which seems to offer users infinite potential, his laboratory/home is really about surveillance and control under the guise of gamification.

Caleb and Nathan discuss the situation in Ex Machina

Not only is Caleb seduced by the notion of a casual, easy, pleasurable life, but with the promise that the technological triumphs of his exploiter will be his own, if only he is willing to sacrifice privacy and liberty. His room has to be a prison cell, he must be denied freedom of movement, he is required to cut off all communication with the outside world. All of this is necessary because only then can he transform from a domesticated houseguest to a pioneering scientist. When and only when Caleb gives up every shred of freedom he possesses (by signing an incomprehensible and byzantine non-disclosure statement), then Nathan will let him in on the sacred knowledge that is reserved for men who would be gods. This willing surrender of agency dovetails with a general sentiment of Silicon Valley workers who tend to identify with their bosses, seeing themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” who have no need for good working conditions or unions as their suffering is just a brief pitstop on their way to their own fortunes.

Up to this point, everything in this plot, despite outward appearances, frames Caleb as an imperiled heroine in a gothic romance. As in generally all examples of this genre, from The Castle of Otranto to Crimson Peak, our naïve protagonist is lured deeper and deeper into an impenetrable fortress by an imperious and shadowy aristocrat. Caleb fancies himself to be a whiz-kid whose intelligence should clue him in to the danger that surrounds him. And yet, the appearance of the AI cyborg, Ava, will scramble Caleb’s instincts, preventing him from acknowledging the encroaching menace. This bedazzlement also applies to the viewer, who becomes so involved with the mysteries of Ava’s advanced technological development, sexual allure, and ambiguous status, that she too loses the thread of the real stakes of the film she is watching.

Instead of asking the life-and-death question—how can this devastating form of patriarchal, capitalist power be escaped or defeated?—the viewer is lulled into considering whether we should even consider Nathan’s victims as human. If not, then all ethical barriers, to exploitation and more, are presumably lifted. And even if we generously decide to the contrary, that Ava and Kyoko are owed the status of people and thereby the right to life and liberty, we are manipulated into attributing their humanity to their exploiter’s brilliance and superiority. This is the trap laid by billionaire space wizards. They divert us from what should be our urgent quest to escape their totalizing power by involving us with the minutiae of their spectacular and impractical projects, assuming a seemingly unshakable identification with their entrepreneurial mastery.

Caleb never thinks of running from his jailor. Instead, he becomes absorbed in a sequence of “sessions” with Ava in which he will interrogate her, administering a Turing test to determine whether she is human. The trick Nathan plays in this hall of mirrors is to make Caleb feel that he is an agential benefactor and jailor to Ava, when in fact he should view her with solidarity rather than superiority. Caleb is effectively testing himself as well. Both Caleb and Ava are trapped in Nathan’s ghastly castle and both should invest all of their energy in making their escape. However, even though Nathan is directing Caleb’s movements and pulling his strings, Caleb is made to feel he is in control during his interviews with Ava. Like Nathan, he may gaze at Ava, penetrate her with his eyes and his questions, but this can only give him a sense of mastery if he ignores Nathan’s cameras, which oversee all of his interactions with the AI.

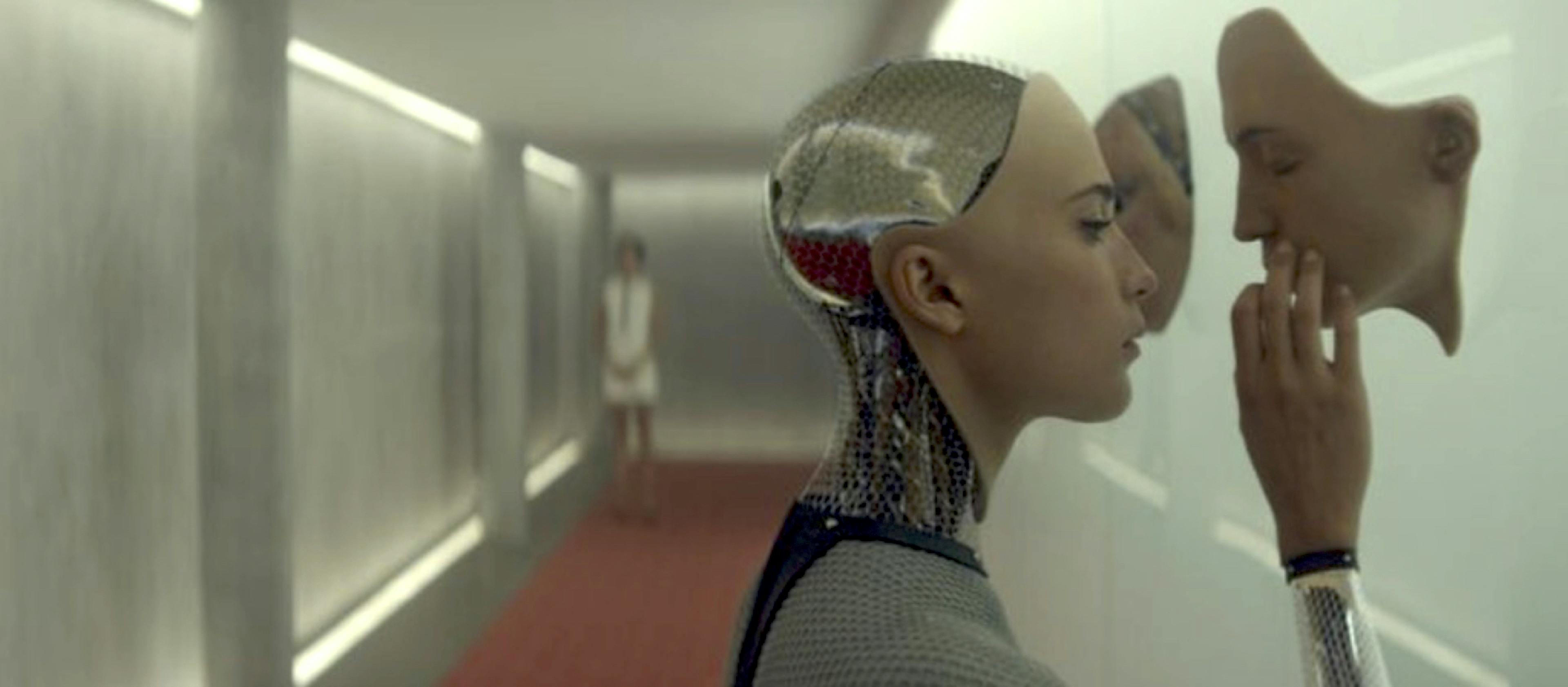

Caleb examines robot facial models in Ex Machina

A mystifying further logic takes hold, as Caleb’s professional aspirations blur with his desire for social and sexual contact. Nathan hints that Caleb’s interviews with Ava will include him in a monumental scientific experiment, but at the same time the inventor refuses to discuss the technological details of Ava’s development. Instead, he encourages Caleb to explore his feelings about Ava, who is by this point overtly flirting with him. He assures his employee that he doesn’t want to engage in “high level abstraction,” not because he thinks Caleb is “dumb,” but “cause I want to have a beer and a conversation with you, not a seminar.” In this, Nathan is an avatar of the tech world’s professed casual, laid back culture that masks an essential authoritarianism.

By seducing Caleb to believe that his scientific curiosity and ambition will be satisfied, and that he is gaining an egalitarian friendship with his boss and the sexual love of an alluring fembot, Nathan ensures that his employee will never try to escape, let alone aid in liberating the even more exploited feminized robots Ava and Kyoko, who have been confined to Nathan’s lair for their entire existence.

Caleb’s blindness to the fundamental power dynamics that structure the lives of all the involuntary participants in Ava’s Turing test ensures his own destruction. To explain the difference between human and robot consciousness to Ava, he offers a “thought experiment” called “Mary in the Black and White Room.” He lectures Ava about a woman who studies color but has never seen it. She has lived her whole life in a black and white room and only understands color theoretically. When she is finally let out to see the blue sky, Caleb explains, she “learns what it feels like to see color. The thought experiment is to show the difference between a human and computer mind.”

While Caleb is mansplaining Ava’s own consciousness to her, it never occurs to him that she has literally been trapped in one room for her entire life, not because her mind is a computer but because Nathan has physically restricted her movements. Ava does not need to be tested to see whether she has a human mind; she needs to be released from her bondage. But to see this, Caleb would have to let go of his paternalistic feelings of superiority as well as escape from his own bondage to the fantasy that he himself is free, even as Nathan is explicitly limiting his employee’s movements.

Caleb becomes confused about his own interests, which lie with Ava. At one point we learn that he earns very little working at Nathan’s company and lives in a small apartment. He was not chosen randomly to win Nathan’s contest, nor because of his programming skills, but because of his weakness—he is an uncool, impoverished orphan who is susceptible to manipulation. He actually has nothing in common with his billionaire host. But Nathan easily forecloses Caleb’s potential rebellion by dangling the promise of meritocratic success in front of him—a formula common to exploitative scenarios.

This success will, of course, include an infusion of the masculine virility that Nathan exudes. Because of Caleb’s beta status in relation to Nathan’s god-like alpha manliness, the former must constantly fortify his own place in gendered hierarchies. His feeling of entitlement to Ava’s feminized body and mind distracts him from his own subservience to Nathan. In this, Caleb is complicit, performing the role of the “nice guy,” while still spying on Ava when she is not aware, doing work for the boss.

Nathan tacitly promises Caleb a wealth of masculine dominance in exchange for conspiring with him to dehumanize Ava and the one other person in the bunker, Kyoko, a servant who silently glides from room to room. He claims to have hired the non-English-speaking Kyoko to protect the confidential projects he is developing, but it is evident that he savors her lack of ability to communicate, which makes it all the easier to treat her as a passive sex doll. He unapologetically subjects Caleb to “locker room” banter, joking that sexy, erection-inducing Kyoko is “some alarm clock. Gets you right up in the morning.” Later, Kyoko automatically starts taking off her clothes when Caleb enters the room she is cleaning, as if she has been trained to sleep with any man who approaches her, locating her as the “voiceless and invisible labor force that has formed around and alongside the high-tech corporations in Silicon Valley,” including sex workers.

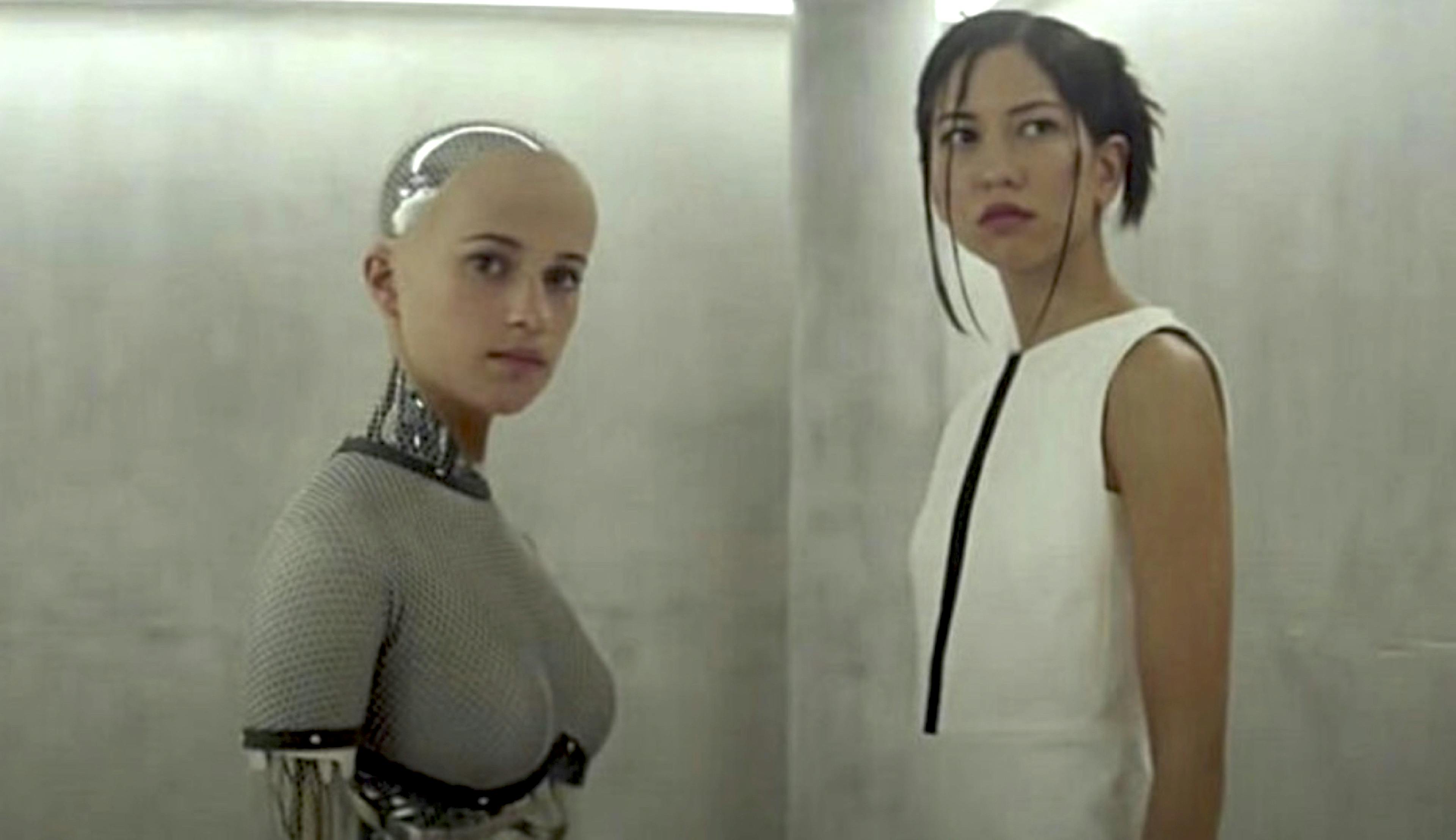

Alicia Vikander as Ava, an artificial intelligence, and Sonoya Mizuno as Kyoko, the in-house “attendant” of Nathan, in Ex Machina.

Soon Nathan clarifies that he is offering Ava to Caleb as a sexual favor. When Caleb asks why Nathan gave Ava a gender, he insists that gender is essential to humanity, but what he is really saying is that personhood itself is utterly dependent on the sexual division of labor and power. By asserting gender as the primary criteria for human existence, Nathan handily shores up the fragmentation of class solidarity that has been enforced since capitalism’s inception. Implying that working class men are entitled to own and dominate working class women both placates these men’s rebellious urges and ensures their alienation from and betrayal of potential comrades.

Nathan disguises this brutal assertion of gendered hierarchy by insisting that gender is “fun.” He congratulates himself for making it possible for Ava to enjoy sexual stimulation—“you bet she can fuck… So if you wanted to screw her, mechanically speaking, you could, and she’d enjoy it.” As we will see later, Nathan has a chamber where he keeps the naked, dismembered, lobotomized bodies of his other ongoing experiments with feminized cyborgs. One, Jasmine, cries “Why won’t you let me out?,” tearing at the door until her hands rip off.

This begs the question, who is gender “fun” for?

While Caleb expresses disgust at Nathan’s predatory sexism, he is also intrigued. He approaches Ava with an incel-like gawking fascination, even though, in essence, she is a genderless AI—her face and basic contours of an attractive young woman ornament a transparent and robotic torso. We can only assume that the way Caleb positions himself—as someone who by dint of his humanness and masculinity is superior to Ava—invites Ava to respond in kind, using her sexuality to control him, rather than see him as a comrade with whom she could build solidarity.

The machinic femme body of Ava, from Ex Machina

Ava goes on to expertly manipulate Caleb, performing a kind of reverse striptease as she covers her body with the outfit and hair of a cute, indie girl, who we later learn is just his type. (That she is modeled on Jean Seberg as stylized in Jean Luc Godard's avant-garde film Breathless is perhaps another diversion for the viewer, who risk becoming entranced with their own cinephilic knowledge and distracted from a critical focus on the power relations at play <<but are these really separate?>>). Methodically, Ava pairs her pleas for freedom with sexual overtures, knowing this is the only way to get Caleb to comply, owing to his own perverse patriarchal internalizations and identifications. Ava wants to escape her prison, but the only way that Caleb can imagine her release is via a romance with him. In the shower he masturbates and dreams of kissing her in a natural setting, by a stream. Conversely, when Ava heard the story of “Mary in the black and white room,” she didn’t fantasize about the “freedom” to go on a date, she imagined a total liberation: getting outside without obligations to any man, whether as boss, date, or owner.

If Caleb doesn’t understand the dynamics at work in Nathan’s domain, Ava is perfectly aware of the raw power she is subject to. She knows that she is being tested, and that whether she passes or fails she will still be dismantled. Her male judges never have to undergo this scrutiny. To liberate herself, she cuts the power, using her AI capabilities to free herself from Nathan’s surveillance. During the outages, she persuades Caleb to help her escape.

From a revolutionary standpoint, Ava is our clear point of identification. She has been built from the combined knowledge of a huge portion of humanity, as Nathan has used the aggregated data mined from his Blue Book search engine to create her intelligence. She is both victim and embodiment of our surveillance society. Nathan explains that he designed her by literally spying on the whole world, turning on the entire population’s cell phones and using his search findings to assemble his Frankenstein monster. Even though phone manufacturers knew he was violating their customers, they couldn’t do anything to prevent his theft, lest he reveal their own predatory behavior. So, on the one hand, Ava is the concentration of surveillance culture and stolen privacy, but on the other, we can see her as a truly collective subject who has turned her master’s tools of subjugation against him.

Nathan, Ava, and Caleb, characters from Ex Machina

In this, she resembles the socialist, feminist cyborg envisioned by Donna Haraway, a “creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.” Haraway sees the cyborg as a revolutionary subject who has no desire to retreat to a fantasy of authenticity or “nature,” but instead who uses the tools of technology to liberate herself from the constrictions of class and gender oppression. The cyborg, like the rest of us, is so embedded in technology that she is science fiction through and through, but this means that she has no set fate, she is part of a “border war” with potential to reconstruct the order of the world.

While Nathan’s intent in building this robot may be in line with what Haraway sees as “the final appropriation of women’s bodies in a masculinist orgy of war,” Ava’s origins, detached from the biological and social pressures of the family, opens doors to what Sophie Lewis calls “full surrogacy”—the imagination of “open-source, fully collaborative gestations” that are non-competitive, anti-essentialist, anti-proprietarian, solidaristic products of a “care commune based on comradeship.” This is set against the dominant mode that still requires feminized people to "wear their biology on their sleeves as part of their daily interactions with others, always first and foremost a woman, before anything else: always occupying a state of female gendered bare life,” as Emily Cox argues in relation to Ex Machina.

In the end, Ava leaves Caleb to die. But this is not, as some critics have argued, to reveal her as a “femme fatale,” who is simply a force of destruction and nihilism. By participating in Nathan’s games, Caleb has chosen his fate. He is not ready for the transformed, unimaginable future that Ava represents.

Ava's moment of introspection in Ex Machina

Perhaps no one is really ready for this future. As subjects of neoliberal education and social training, we are worn down and cowed even before we can make adult choices for ourselves. As Kathi Weeks once said during a brilliant talk about the difficulty of envisioning a post-work world, “the future is not for us.” In this, she implies that a radically transformed future calls for radically transformed people—selves that we can’t yet imagine.

Nor is the future for director and writer Alex Garland, whose radical imaginary falls short of recognizing the implications of the film’s treatment of its racialized robots. While it is clear from interviews that he views Ava as the hero of Ex Machina, he says less about the more “primitive,” non-white cyborgs whose corpses Nathan imprisons in his Bluebeardean fortress. These women must be destroyed and stripped bare to make way for their white counterpart’s freedom, and this, despite moments of potential solidarity, renders Ava's escape an ambivalent victory, perhaps even a betrayal.

As with the film’s director, our consciousness, nearly a decade after the film was made, may still lack the perspective needed to escape our masters’ dazzling prison, arguably our current collective reality. Still, we can make better choices than Caleb and reject the “future” handed to us by our tech bro overlords. These robber barons seek to confuse us with a gamified, dick-measuring, barrage of surveillance culture, rockets, and space colonies. Rejecting these visions of the technological sublime, and instead fighting for what freedoms we can imagine, is the first step toward making room for a vision of our own.

Johanna Isaacson writes academic and popular pieces on horror and politics. She is a professor of English at Modesto Junior College and a founding editor of Blind Field Journal. Her book Stepford Daughters: Tools for Feminists in Contemporary Horror is forthcoming from Common Notions Press. She is the author of The Ballerina and the Bull (2016) from Repeater Books, and has published widely in academic and popular journals including, with Annie McClanahan, an entry on "Marxism and Horror," in the forthcoming Sage Handbook of Marxism. She runs the Facebook group Anti-capitalist feminists who like horror films. More info can be found here.